The Inconvenient Truth about Lisa Shultz's Article

Maybe the Kids Say They Are Trans or Queer Because They Really Are?

Introduction:

In her article "Reasons Kids Say They Are Trans or Queer,1" Lisa Shultz raises important questions about the factors influencing transgender and queer identification in youth. While it is crucial to explore the complexities of gender identity development, it is equally important to rely on evidence from reputable, peer-reviewed, and/or expert consensus when evaluating the validity of proposed causes. As a parent or layperson, failure to do so can lead to the falling victim to confirmation bias via unsupported claims and misinformation. Indeed, this is how many who peddle books, subscriptions, and speaking events profit from the insecurities and fears of those who simply do not know, or do not understand, the data and science that is out there today.

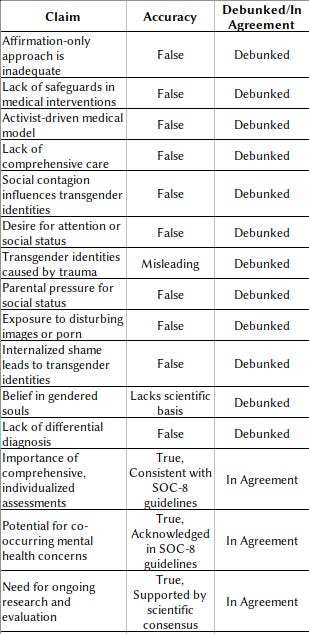

This rebuttal will address the main points raised in Shultz's article, including the alleged inadequacy of the "affirmation-only" approach, the lack of safeguards in medical interventions, the activist-driven nature of the current medical model, the lack of comprehensive care, and the call for better care. By examining each of these claims through the lens of the relevant research and data, including the recent Standards of Care for the Health of Transgender and Gender Diverse People, Version 8 (SOC-8), we aim to provide a more accurate and evidence-based understanding of the care for transgender and gender-diverse individuals.

The SOC-8 guidelines, developed by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH), represent a comprehensive, evidence-based framework for providing care to transgender and gender-diverse individuals across the lifespan. By relying on these guidelines and other peer-reviewed research, we can ensure that our understanding of gender identity development and the provision of care to transgender and gender-diverse youth is grounded in the best available science and expert consensus. I recognize that this is not free from controversy or criticism, and the fact is that many of these criticisms stem from misunderstandings or deliberate misinterpretations of the guidelines. The so-called 'WPATH Files' controversy, based on selectively leaked internal communications, does not invalidate the scientific integrity of the SOC-8. These files represent normal scientific discourse and debate that occurs during the development of any major guidelines, not evidence of misconduct or bias. For those who wish to argue on other merits, the points most often raised are addressed and can be understood through this article at Science Based Medicine.2

Before delving into the specific claims made in Shultz's article, it is important to address the problematic framing of gender-affirming care in her introduction. Shultz suggests that the idea of providing medical interventions to transgender youth is 'overwhelming to think about or visualize,' leading people to 'look away and hope it works out okay.' This emotionally charged language dismisses the real needs and experiences of transgender individuals seeking care. While concerns about the long-term effects of these interventions are valid and warrant ongoing study, characterizing them as too distressing to even consider ignores the well-documented benefits of gender-affirming care for the majority of transgender youth. It is crucial that we approach this with empathy, nuance, and a commitment to evidence-based practice, rather than relying on knee-jerk emotional reactions.

“Facts do not cease to exist because they are ignored” - Aldous Huxley

Point 1: Multiple factors

One of the main issues with Shultz's article is that it presents anecdotal evidence and unsupported speculations as if they were established facts. Here I attempt to break them down, without going too far in depth as there are many she states. We ignore “combinations thereof” idea, as that seems to be a hail-Mary catch-all in the event any one gets disproven or debunked, then it might be it’s combination with another thing!

Confusion after exposure to trans or queer persons, reading material, porn, or internet/social media content

For example, she suggests that exposure to "disturbing images or porn," including drag queens and "scantily clad people," can cause confusion and lead to transgender identification. However, I could find no studies or evidence that supports this claim. One could make a fair counter argument by positing the following: “If exposing a child to pornography, drag queens, scantily clad people, or SEM caused kids to be trans, then one would expect trans identified teens to a majority, and not the minority we see today.”

Internalized Homophobia/Gay Shame/Trauma

Similarly, while internalized homophobia and trauma are real issues that can impact an individual's mental health and sense of self, there is no evidence to suggest that they are primary causes of transgender identification. A study by Natalia Ramos and Mollie C. Marr3 found that experiences of internalized homophobia and trauma were not significantly associated with transgender identity, and that these experiences were common among both transgender and cisgender individuals. Interestingly, that same study points out the following:

“The rise of anti-transgender bills around the United States further marginalizes TGD youth, who already face high rates of victimization and discrimination in home and school settings. Public restriction or loss of civil rights among the LGBTQ community contributes to feelings of stigma, hopelessness, internalized homophobia/transphobia, and poor self-image.”

ROGD, Social Contagion, AGP

Shultz also cites discredited theories such as “Rapid Onset Gender Dysphoria (ROGD)”, “Social Contagion”, and “Autogynephilia (AGP)”, which have been widely criticized by experts in the field and rejected by major medical organizations. The original study proposing ROGD4 has been criticized for its methodological flaws and lack of scientific rigor5. Further studies have not been able to find any evidence to support ROGD or that “Social Contagion” occurs with transgender identification.6 Similarly, the concept of AGP has been debunked as a valid explanation for transgender identity, with studies finding no evidence to support this theory7 .

Body Discomfort and Dysphoria

Shultz raises the issue of body discomfort and dysphoria, particularly among teenage girls, and suggests that "affirmation-only policies" prevent practitioners from helping individuals feel comfortable with their "natural body." However, this claim misrepresents the nature of gender-affirming care and the experiences of transgender individuals. This one will require a bit of text to break down, as it is a multi-faceted claim that needs to be broken down and addressed.

First, it is important to recognize that body discomfort and dysphoria are not unique to transgender individuals. Many cisgender people, particularly adolescents, experience discomfort with their bodies and the changes associated with puberty. However, for transgender individuals, this discomfort is often specifically related to the incongruence between their gender identity and their body, rather than general dissatisfaction with their appearance or the effects of puberty8 .

Second, the claim that "affirmation-only policies" prevent practitioners from helping individuals feel comfortable with their bodies is not supported by evidence. Gender-affirming care, as outlined in the Standards of Care for the Health of Transgender and Gender Diverse People, Version 8 (SOC-8), involves a comprehensive, individualized approach that includes psychological support, social transition, and medical interventions when appropriate9. The goal of gender-affirming care is not to "enable a dislike of the body," but rather to alleviate gender dysphoria and support the individual's overall well-being.

In fact, the SOC-8 specifically emphasizes the importance of providing supportive, non-judgmental care that helps individuals explore their gender identity and make informed decisions about their transition. The guidelines state, "The role of the health professional is to provide information, support, and guidance to help individuals make informed decisions about their gender identity and expression, not to direct or determine their identity"10.

Third, while social media and unrealistic beauty standards can certainly contribute to body dissatisfaction and dysphoria, it is important not to conflate these issues with the experiences of transgender individuals. Transgender people do not identify as transgender because of social media filters or a desire to conform to a particular body type. Rather, their gender identity is a deeply felt, innate sense of self that is not determined by external influences or pressures11.

Finally, it is crucial to recognize that gender-affirming care, including medical interventions such as hormone therapy and surgery, can significantly improve the mental health and quality of life of transgender individuals who experience dysphoria1213. These interventions are not about "altering" the body to conform to a particular ideal, but rather about aligning the individual's body with their gender identity to alleviate distress and promote well-being.

While body discomfort and dysphoria are real issues that can impact transgender individuals, Shultz's characterization of "affirmation-only policies" and the nature of gender-affirming care is misleading and not supported by evidence. By providing a more comprehensive, evidence-based understanding of these issues, we can better support transgender individuals in their journey towards self-acceptance and well-being.

So when discussing the factors influencing transgender and queer identification in youth, it is essential to rely on well-designed, peer-reviewed studies and the consensus of experts in the relevant fields. Anecdotal reports, speculation, and debunked hypotheses should not be presented as valid explanations, as they can contribute to the spread of misinformation and stigma surrounding transgender and gender-nonconforming individuals.

Other Factors - Attention, Status, Queer Theory, and “Trapped Souls,” etc.

Other factors mentioned in the article, I won’t list them all out here exhaustively, such as a desire for attention or elevated status for parents, belief in queer theory, or the concept of "trapped souls," and others are not supported by scientific evidence and do not represent recognized factors in transgender identification. In fact, as far as I can tell, this is all based on pure speculation or “common sense reasoning” and falling into either/or/both confirmation bias coupled with “post hoc ergo propter hoc” - that is that correlation does not imply causation.

Instead of focusing on unsupported or discredited theories, it is crucial to prioritize evidence-based approaches that support the health, well-being, and autonomy of transgender and queer youth. This includes providing access to affirming healthcare, creating safe and inclusive environments, and promoting further research to better understand the complexities of gender identity development.

And in all of this searching and looking for all these various “causes” and “reasons” we miss the most obvious, and the one with the most empirical evidence that stands to the rigors of science, scrutiny, and study: they are trans or queer because they are simply born that way.

Point 2: Inadequate Safeguards

Shultz expresses concern about the lack of protective safeguards in the US before medicalization occurs and questions the potential harm from puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, and surgeries, particularly in the context of treating transgender and gender-diverse adolescents and children. However, the SOC-8 provides detailed guidelines and safeguards for the use of these interventions in young people, emphasizing the need for comprehensive assessments, informed consent, and ongoing monitoring to ensure patient safety and well-being.

The SOC-8 recognizes that the treatment needs of transgender and gender-diverse adolescents and children may differ from those of adults and requires a more cautious and individualized approach. The guidelines state, "The treatment of adolescents involves unique considerations that may not apply to adults, and the treatment of prepubertal children involves different approaches than the treatment of adolescents" (SOC-8, p. S49).

For adolescents seeking gender-affirming medical interventions, the SOC-8 recommends a comprehensive assessment process that includes "a thorough evaluation of the adolescent's gender identity, mental health, and psychosocial functioning" (SOC-8, p. S51). This assessment should be conducted by a qualified mental health professional with expertise in working with transgender and gender-diverse youth.

The SOC-8 also emphasizes the importance of informed consent and shared decision-making when considering medical interventions for adolescents. The guidelines state, "Before any medical intervention is considered, health professionals should ensure that the adolescent has the capacity to make an informed decision and that the potential benefits of the intervention outweigh any potential risks" (SOC-8, p. S52).

For prepubertal children, the SOC-8 recommends a supportive, gender-affirming approach that focuses on social transition and does not involve medical interventions. The guidelines state, "The treatment of prepubertal children involves supporting the child's exploration of their gender identity and providing a safe and affirming environment for them to express their gender" (SOC-8, p. S49).

The SOC-8 also highlights the importance of ongoing monitoring and follow-up care for transgender and gender-diverse adolescents and children who receive medical interventions. The guidelines recommend regular check-ins with healthcare providers to assess the effectiveness of treatment, monitor for any adverse effects, and provide ongoing support14.

By providing detailed guidelines and safeguards for the treatment of transgender and gender-diverse adolescents and children, the SOC-8 directly addresses Shultz's concerns about inadequate protections and potential harm. The standards prioritize comprehensive assessments, informed consent, shared decision-making, and ongoing monitoring to ensure the safety and well-being of young patients.

Point 3: Activist-Driven Medical Model

Shultz suggests that the current medical model for treating gender-related distress in children and adolescents is driven by activists rather than a commitment to the medical oath of "Do No Harm." However, it is important to note that the phrase "do no harm" is not actually part of the Hippocratic Oath or any other formal medical oath. While the principle of non-maleficence, which emphasizes the avoidance of harm, is a fundamental tenet of medical ethics, it is not the only consideration in providing care15.

Shultz sets up a false dichotomy between uncritical 'trans allies' and unfairly demonized 'questioners,' oversimplifying the complex realities of gender identity development and best practices in care. It is possible and necessary to affirm transgender individuals while acknowledging the importance of thorough assessments, research, and nuanced dialogue. Questioning specific theories, like ROGD, is not inherently transphobic, but these questions must be grounded in evidence and clinical guidelines, not assumptions or biases.

The SOC-8 is developed by healthcare professionals and experts in transgender health, based on the latest research and clinical best practices. The guidelines are rooted in evidence-based care and the principles of medical ethics, including respect for patient autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice16. The SOC-8 advocates for individualized, patient-centered care that prioritizes the overall well-being and quality of life of transgender and gender-nonconforming individuals.

The development of the SOC-8 involved a rigorous process of scientific review, stakeholder engagement, and expert consensus-building. The guidelines state, "The SOC-8 is based on the best available science and expert professional consensus. The recommendations in the SOC-8 are informed by evidence from peer-reviewed literature, input from clinicians with vast experience in this field, and crucial feedback from transgender and gender diverse people" (SOC-8, p. S3).

By suggesting that the current medical model is driven by activists, Shultz dismisses the expertise and integrity of the healthcare professionals who have developed and endorsed these guidelines. This claim undermines the evidence-based nature of the SOC-8 and the commitment of healthcare providers to the well-being of their patients.

Point 4: Lack of Comprehensive Care

Shultz claims that the current model does not investigate the complexity beneath gender identity development, suggesting that factors such as confusion, internalized homophobia, trauma, and social contagion are not adequately explored before medical interventions are offered. However, the SOC-8 recognizes the complexity of gender identity and recommends individualized, comprehensive care that considers each patient's unique needs and circumstances.

The SOC-8 emphasizes the importance of a thorough assessment process that explores the psychological, social, and medical aspects of gender identity development. The guidelines state, "A comprehensive assessment should include an evaluation of the individual's gender identity, gender expression, and the impact of gender dysphoria and gender incongruence on their mental health and well-being" (SOC-8, p. S27).

Regarding the specific factors mentioned by Shultz, it is important to note that some of these claims are not supported by evidence. For example, the concept of social contagion influencing gender identity has been widely debunked and is not recognized as a valid theory by major medical and mental health organizations17. Similarly, the notion that confusion or exposure to gender-related content can cause someone to become transgender is not supported by scientific evidence18.

However, the SOC-8 does acknowledge the importance of addressing co-existing mental health concerns, such as internalized homophobia or trauma, as part of a comprehensive assessment. The guidelines state, "Mental health professionals should assess for and address any co-existing mental health concerns, such as anxiety, depression, or trauma, that may be contributing to an individual's distress related to their gender identity" (SOC-8, p. S28).

The SOC-8 also emphasizes the importance of differential diagnosis in the assessment process. Differential diagnosis involves considering and ruling out other potential causes of an individual's symptoms or concerns before arriving at a diagnosis of gender dysphoria or recommending medical interventions. The guidelines state, "A comprehensive assessment should include a differential diagnosis to rule out other possible explanations for the individual's gender-related concerns, such as body dysmorphia, internalized homophobia, or trauma" (SOC-8, p. S29).

By conducting a thorough differential diagnosis, healthcare providers can ensure that an individual's gender-related concerns are not better explained by other factors and that medical interventions are appropriate and necessary. The SOC-8 recognizes that while some individuals may experience co-existing mental health concerns or other factors that influence their gender identity development, these factors do not negate the validity of their gender identity or the potential benefits of gender-affirming care (SOC-8).

To summarize this point, while Shultz raises concerns about the lack of comprehensive care and the potential influence of various factors on gender identity development, the SOC-8 directly addresses these issues by recommending a thorough, individualized assessment process that includes differential diagnosis. The guidelines recognize the complexity of gender identity development and the importance of addressing co-existing mental health concerns, while also acknowledging that some of the factors suggested by Shultz, such as social contagion, are not supported by scientific evidence.

Point 5: Call for Better Care

Shultz calls for a united effort to provide better care to children and vulnerable adults, emphasizing the need to pause and investigate the complexity beneath gender identity development before endorsing irreversible medical interventions. This is a valid concern, and we agree that it is crucial to prioritize the well-being of transgender and gender-diverse individuals by providing comprehensive, evidence-based care that considers the complexity of gender identity development.

While Shultz cites the Cass Review as evidence against medical interventions for gender dysphoria, this misrepresents the report's findings and scope. The Cass Review identified areas for further research but did not recommend withholding interventions entirely. More importantly, the SOC-8 guidelines represent a more comprehensive, up-to-date synthesis of the evidence on gender-affirming care. Based on rigorous scientific review and expert consensus, the SOC-8 provides a framework for the safe and effective use of medical interventions within a context of individualized care.

The SOC-8 supports this call for better care by emphasizing the importance of thorough assessments, interdisciplinary collaboration, and individualized care plans. The guidelines state, "The assessment and treatment of gender dysphoria and related concerns should be a collaborative effort involving mental health professionals, medical providers, and other relevant stakeholders, such as family members and schools" (SOC-8, p. S26).

By bringing together professionals from various disciplines and considering the unique needs and circumstances of each individual, healthcare providers can ensure that the care they provide is comprehensive, evidence-based, and tailored to the specific needs of the patient. The SOC-8 also emphasizes the importance of informed consent and shared decision-making, ensuring that patients and their families are fully aware of the potential benefits and risks of any medical interventions (SOC-8).

However, it is important to note that the SOC-8 guidelines already provide a framework for the kind of comprehensive, evidence-based care that Shultz is calling for. The guidelines are based on the best available scientific evidence and expert consensus, and they are designed to promote the health and well-being of transgender and gender-diverse individuals across the lifespan (SOC-8).

To ensure that transgender and gender-diverse individuals receive the best possible care, it is essential that healthcare providers are trained in the use of the SOC-8 guidelines and are knowledgeable about the unique needs and experiences of this population. This includes not only medical and mental health professionals but also nurses, social workers, and other support staff who may interact with transgender and gender-diverse patients.

By increasing education and training for healthcare providers, we can help to ensure that the comprehensive, evidence-based care outlined in the SOC-8 is widely available and accessible to all transgender and gender-diverse individuals who need it. This may involve incorporating the SOC-8 guidelines into medical and nursing school curricula, providing continuing education opportunities for practicing professionals, and developing specialized training programs for those who work with transgender and gender-diverse patients19.

In addition to education and training, it is also important to advocate for policies and practices that support the implementation of the SOC-8 guidelines and promote the health and well-being of transgender and gender-diverse individuals. This may include efforts to increase insurance coverage for gender-affirming care, reduce barriers to accessing care, and protect the rights and dignity of transgender and gender-diverse individuals in healthcare settings20.

By working together to implement the SOC-8 guidelines, increase education and training for healthcare providers, and advocate for supportive policies and practices, we can provide the kind of comprehensive, evidence-based care that Shultz is calling for and ensure that transgender and gender-diverse individuals receive the support and care they need to thrive.

Conclusion:

Shultz's characterization of a 'trans doctrine' pushing uncritical affirmation and medical intervention is a strawman that does not reflect actual evidence-based practices in the SOC-8, endorsed by major medical organizations. There is no singular 'trans doctrine,' but rather a growing body of research supporting comprehensive, individualized care, including thorough assessments and a range of interventions based on each person's unique needs. In contrast, the 'gender critical' position Shultz advocates is a loosely defined collection of ideas, some based on discredited theories or unsupported claims, that all seem to culminate into the common fearmongering and harmful call to deny trans validity and science, reject requested names (or renaming) and pronouns, and protect your kid from any/all access to anything transgender positive or affirming care and not a coherent, evidence-based approach.

While Lisa Shultz's article raises important questions about the care of transgender and gender-nonconforming youth, most all of her claims are not supported by the current evidence and best practices in transgender healthcare. The claims that were supported by current evidence and best practices were misrepresented, and when considered in context and to the full breadth they were intended, work to defeat her own argument. The SOC-8 guidelines provide a comprehensive, evidence-based framework for the care of transgender and gender-diverse individuals, addressing concerns about inadequate safeguards, activist-driven care, lack of comprehensive assessments, and the need for better care.

Throughout this rebuttal, we have demonstrated how the SOC-8 guidelines and other relevant research contradict the claims made in Shultz's article. The SOC-8 emphasizes individualized, patient-centered care that prioritizes the safety, well-being, and autonomy of transgender and gender-nonconforming individuals. It recognizes the complexity of gender identity development and advocates for a thorough, multidisciplinary approach to assessment and treatment.

While there is an ongoing need for research and education to better understand and support the needs of transgender and gender-diverse individuals, the current evidence base is robust and supports the efficacy and necessity of gender-affirming care in improving mental health outcomes and overall well-being for this population.

As we work to support transgender and gender-nonconforming youth, it is crucial that we rely on evidence-based practices, expert consensus, and the lived experiences of the transgender community. We must prioritize comprehensive, individualized care that respects the autonomy and diversity of transgender individuals and work towards creating a more inclusive and affirming society for all.

We call upon healthcare providers, policymakers, and the general public to support the implementation of the SOC-8 guidelines and to advocate for policies and practices that promote the health and well-being of transgender and gender-diverse individuals. By working together and relying on the best available science, we can ensure that transgender and gender-diverse youth receive the care and support they need to thrive.

I wrote this rebuttal on 2024/09/01 - This was later cross-posted to pittparents.com on 2024/09/10. I did update the draft, but I will spare you the link to either site. ↩

Eckert, A., & McLamore, Q. (2022, November 4). Cutting through the lies and misinterpretations about the updated standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people. Science. https://sciencebasedmedicine.org/cutting-through-the-lies-and-misinterpretations-about-the-updated-standards-of-care-for-the-health-of-transgender-and-gender-diverse-people/ ↩

Ramos, N., & Marr, M. C. (2023). Traumatic stress and resilience among transgender and gender diverse youth. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 32(4), 667-682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2023.04.001 ↩

Littman, L. (2018). Parent reports of adolescents and young adults perceived to show signs of a rapid onset of gender dysphoria. PLoS ONE, 13(8), e0202330. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202330 ↩

Restar, A. J. (2020). Methodological critique of Littman's (2018) parental-respondents accounts of "rapid-onset gender dysphoria." Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(1), 61-66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-1453-2 ↩

Ashley, F. (2020). A critical commentary on 'rapid-onset gender dysphoria.' The Sociological Review, 68(4), 779-799. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026120934693 ↩

Serano, J. M. (2020). Autogynephilia: A scientific review, feminist analysis, and alternative 'embodiment fantasies' model. The Sociological Review, 68(4), 763-778. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026120934690 ↩

Coleman, E., Radix, A. E., Bouman, W. P., Brown, G. R., de Vries, A. L. C., Deutsch, M. B., Ettner, R., Garofalo, R., Karasic, D. H., Klink, D., Monstrey, S., Rachlin, K., Schechter, L., Tangpricha, V., van Trotsenburg, M., & Winter, S. (2022). Standards of Care for the Health of Transgender and Gender Diverse People, Version 8. International Journal of Transgender Health, 23(sup1), S1-S259. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644 ↩

Ibid. ↩

Ibid. p. S25 ↩

Turban, J. L., & Keuroghlian, A. S. (2018). Dynamic gender presentations: Understanding transition and "de-transition" among transgender youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 57(7), 451-453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2018.03.016 ↩

Turban, J. L., Beckwith, N., Reisner, S. L., & Keuroghlian, A. S. (2020). Association between recalled exposure to gender identity conversion efforts and psychological distress and suicide attempts among transgender adults. JAMA Psychiatry, 77(1), 68-76. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2285 ↩

Olson, K. R., Durwood, L., DeMeules, M., & McLaughlin, K. A. (2016). Mental health of transgender children who are supported in their identities. Pediatrics, 137(3), e20153223. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-3223 ↩

See 7 Above. ↩

Beauchamp, T. L., & Childress, J. F. (2019). Principles of biomedical ethics (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. ↩

Ibid. ↩

Ashley, F. (2022). The clinical irrelevance of "desistance" research for transgender and gender creative youth. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 9(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000504 ↩

See 10 Above. ↩

Safer, J. D., Coleman, E., Feldman, J., Garofalo, R., Hembree, W., Radix, A., & Sevelius, J. (2016). Barriers to healthcare for transgender individuals. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Obesity, 23(2), 168-171. https://doi.org/10.1097/MED.0000000000000227 ↩

Ibid. ↩